ANALYSIS: Keeping a roof over your head keeps getting more expensive, and it doesn’t look like any respite is coming in 2022. Recent inflation numbers showed nationwide rents rose 3.8% per annum last year, the fastest growth in the current rental series since it began in 1999. High levels of residential building activity haven’t yet caught up with demand for housing, and landlords’ costs associated with owning rental property are rising. It’s the bottom of the market that’s being squeezed the most, but real long-lasting solutions for New Zealand’s rental woes won’t be quick fixes.

After creating headlines in recent years for eyewatering rents, you’d think Auckland might again be leading the rental price pack higher. You’d be wrong.

Although still rising at 2.0%pa, Auckland actually saw the slowest growth in rents by region in December. A slight fall in population, more central city apartments becoming available, with fewer international students, inner-city workers, and less demand for Airbnbs all prevented a more substantial rental rise in the Super C city.

But the weaker Auckland growth masked rising rents around the rest of New Zealand. Compared to pre-pandemic (December 2019), Auckland rents are only up 3.3%, less than half the 6.8% increase nationally. Better economic activity, more regional migration, and intense housing market pressures have seen rents across the provincial North Island rise 13% and 11% in Wellington.

Start your property search

Of grave concern is the pressure being felt at the bottom end of the rental market. At the end of December 2021, there were 25,525 families on the Housing Register nationally, more than five times higher than the 4,771 recorded in December 2016.

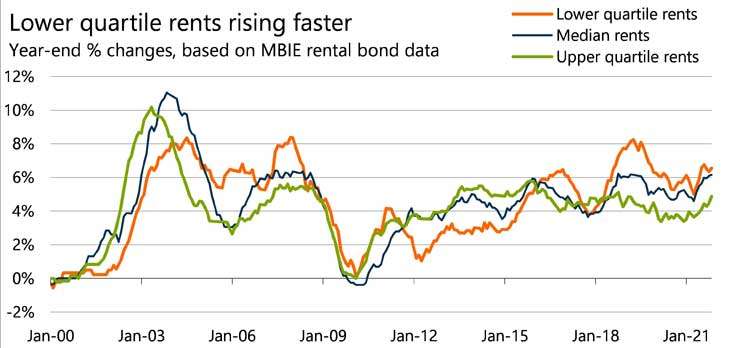

It’s becoming clearer why the Housing Register has exploded, as renters on limited incomes are pushed out of the rental market as prices rise at the bottom end. Infometrics analysis of MBIE data shows that lower quartile rents (rents towards the lower end of the market) have risen 34% since 2016. This increase is far faster than the 29% increase in median rents, and the 23% rise in upper quartile rents (towards the top end of the market).

Essentially, lower-income families, in cheaper rentals, are getting squeezed the hardest, and many can’t afford the increases. As rents have risen across the board and regional migration remains high, renters are moving further away from the main centres to find accommodation, increasing demand, and pushing up rents across the provinces, and displacing previous tenants who paid lower rent.

Even with this displacement occurring, and the population rising, a lack of rentals means that turnover of rentals is slowing. This slowdown in turnover has been happening since 2017. The number of bonds lodged annually has fallen from a peak of 178,236 in the year to September 2016 to 157,614 in the year to February 2020.

By November 2021, bond lodgements were lower still, driven by lockdowns and incomplete reporting for the year. But even in mid-2021, annual bond numbers were still down 12% from levels seen five years ago. The total number of active bonds in the rental market grew at a paltry 1.5% over the year to November 2021, less than one third of the 4.7%pa average growth in active bonds over the last 27 years.

We’re simply not creating enough rental stock to house everyone. With rents rising, and mortgages becoming harder to get, it’s taking longer to save for a deposit, meaning that Kiwis are finding it even more difficult to pole vault onto the bottom rung of the housing ladder. With broader inflation picking up, just keeping a roof over your head is a financial nightmare.

Economist Brad Olsen: “Policy-makers are likely to face some tough choices in 2022.” Photo / New Zealand Herald

Fast- rising rents are a critical issue to address, but any actions must actually address the problem, rather than the symptoms, and not create even more headaches.

At its simplest, prices for rents go down when there’s options out there for renters, and landlords have to compete to get tenants into their property. If someone won’t rent a house, the price will have to drop until someone will take it, or the landlord will sell as they won’t have money coming in to pay a mortgage.

Current policy settings will help. Tax incentives now heavily favour new builds for investors, with retained interest deductibility, less stringent lending requirements, and a shorter bright-line test period. We need to keep this focus on adding more, not playing musical chairs with our existing stock. A prioritisation on building more housing is needed, with a sustained commitment to build up and out across the country. There’s a lot of building planned, but with resources stretched, setting out that housing comes before other lofty building projects might be needed. Access to building products, speedier and less onerous consenting, and actual money for pipes and infrastructure, not just consenting paperwork, would be good too.

None of these solutions are quick fixes. Policy- makers are likely to face some tough choices in 2022 about the short-term support they can provide to help pay for rising rents for those at the bottom. But we’ve got to keep going with the longer-term solutions to ensure we actually solve our housing problems, not just plaster over them with short-term patch-up jobs.

- Brad Olsen is is a principal economist and director at data analysts Infometrics.