Matamata-Piako, where international tourists once flocked to the Hobbiton film set, is one of the hardest hit pockets in the regions for unemployment as the impact of the loss of overseas visitors hits home.

Other hotspots, like Queenstown, are suffering from a huge tourism shock leading to high numbers of jobless.

Brad Olsen, a senior economist at market analysts Infometrics, believes unemployment will have a negative effect on the housing market nationwide but areas that rely on the international dollar will feel it hardest.

That includes Matamata-Piako in the Waikato where the impact is “big enough".

Start your property search

"If we look at Matamata-Piako as a district, 31 percent of their tourism spending to the year March 2020 was from international visitors. Now, that was higher than the entire Waikato region of 26 percent from international visitors.”

While regions like the Waikato have strong primary sectors, pockets within pockets will have severe unemployment-related issues, he says.

Otago, also with a strong primary sector, is faring slightly better but Queenstown is a hard-hit pocket within the region.

Queenstown, he says, saw a 1000 per cent increase in the number of job seekers since Covid-19 - "from 29 before lockdown to 450 or so just after lockdown”.

There is more pain to come across the country, Olsen says, with Infometrics forecasting 250,000 job losses over the next couple of years.

Wage subsidies and mortgage relief will tide homeowners over but in a sense this delays the impact, he says.

“For some businesses, they are going to wait and see where everything lands and there is a growing optimism that maybe we’ll be able to get a trans-Tasman bubble operating, and of course we’ll get tourism activity going back around New Zealand in terms of that domestic market.

“But in my mind there’s still a huge amount of pain in the likes of Queenstown, simply because of the concentration effect," Olsen says.

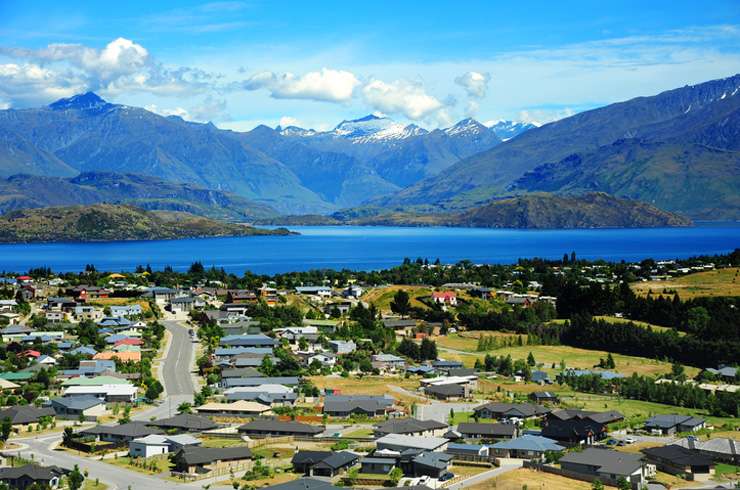

Lake Wanaka in Queenstown and Lakes District. Jobless numbers in the region have risen dramatically since the end of March. Photo / Getty Images

“So much of the economy is based on tourism and so much of it is financed by that international tourism spend – there’s simply not enough money.”

Even if every New Zealander decided to take a huge range of holidays that still would not make up half the international tourist spend, Olsen says.

Other areas feeling the pain include Northland which already had the largest proportion of the working age population on a benefit before Covid-19 arrived and now has even more people out of work – in January 8.2 per cent were jobless and now the figure is 10.2 per cent with 2200 additional people now unemployed.

“That’s just over one in every ten people in Northland walking around aged between 18 and 64 currently out of a job. That’s a very large number.

“What is clear in the numbers is that no matter where you are, this is affecting everyone and it’s going to be less of a question of who’s affected and who’s not and more the degree, or the power, of the shock.”

Just over 40,000 additional people around the country went on the job seeker benefit in the last six weeks or so, Olsen says.

Fewer workers means less spending in local economies, including by businesses which have closed or downsized not buying from other businesses leading to a snowball effect.

Tourism is a stark example of where the pain is being felt as the sector supports just over 9 per cent of the country’s entire workforce.

When that workforce is not employed there’s a huge impact on all the supply chains, as well as cafes, venues and air travel.

“Almost every region bar two (Southland and Otago) have had a one percentage increase in their working age population who is currently on a job seeker support so there are some big changes coming through," Olsen says.

Russell in the Bay of Islands in Northland. The lack of overseas visitors will have an impact on business confidence and ultimately the housing market. Photo / Getty Images

“The numbers are startling. If we look at some of our bigger regions, such as the likes of the Waikato, you’re talking nearly 4300 additional people. Even Wellington as a region has 3700.

“That’s the thing that makes it real to people. These are real jobs. Real people are going to find it really difficult moving forward to afford the same level of spending they previously did.”

For housing, that means some people won’t be able to afford their rent or to pay their mortgage.

While there may well be forced sales of homes, Olsen says there may be a lot more people who are not necessarily at the point of being forced but who feel they are so close they will sell anyway.

“That downsizing effect will see prices start to come down in our minds around 11 per cent in the next year or two. That won’t be shared equally across the country as there are some areas that are slightly more vulnerable. I don’t want to pick on Queenstown but it is certainly one of the areas that is facing some tougher times.”

And while low interest rates and the removal of the LVR restrictions are positives, they are not a panacea with credit availability tougher than ever and banks wanting to understand people’s financial position and job prospects before they lend.

Olsen says Infometrics is one of the most pessimistic forecasters but is being realistic. “We’re expecting 250,000 job losses over the next year or two and that’s quite sobering. It’s a quarter of a million Kiwis that might be out of work,” he says.

While the numbers out of work were increasing at a slower pace in alert level two, that pointed to the wage subsidy doing it’s job but once that ends next month there will be another spike in jobless numbers, and when the extension of the subsidy ends in September/October there will be a further spike.

The path back is not an easy one, Olsen says.

“We had unemployment that rose to 6.7 per cent after the Global Financial Crisis. Only in December last year did we get it to four per cent – just over two-and-a-half percentage points took us a decade and you wonder if we do hit 10 per cent how much longer does it take to get those six percentage points off again.”

Despite the grim scenario, he says it could be worse.

“If we look at the US, the UK, and similar, we’re in a better position to get things going and the support the Government has given has delayed a lot of the immediate effects we were worried about to start with," he says.

“If we can do that for the next nine months we might avoid the worst of it – I’m not saying after nine months everything is fine but we might avoid the worst of that very sharp dip.”

Olsen expects “jerky” results in the housing market and says we probably won’t see a trend for the next six or nine months.