When Paul and Vivienne van Dorsten rented a home at Stonefields, the east Auckland suburb carved out of a former stone quarry, it was meant to be temporary. “We never ever would have considered [buying at Stonefields] because of the stigma of intensive housing,” says Paul van Dorsten. Little did he know that he would eventually become a big fan of the suburb and chair of the Stonefield Residents Association.

Stonefields is a master planned community on brownfields land, meaning it has previously been used for other purposes. In this case, Stonefields started life as a quarry. Construction began in 2008 and evolved over the next decade with more than 2,500 apartments, and homes built across 110ha. When the development was launched prices for standalone homes were well below $1 million, but they are now pushing towards the $3m mark, with the suburb’s average property value sitting at $1.8m, up 25% ($362,000) on a year ago.

The van Dorstens had previously owned architecturally designed homes in Remuera and Orakei and fully expected to return to their old stomping ground. “One day my wife said, ‘I like living here.’ And I replied, ‘So do I.’ We just loved the community around us.”

The couple then bought a four-bedroom, two-bathroom ready built home by Fletcher Living and are even happier now than they were eight years ago when they first found themselves living in Stonefields. “What's evolved over the years is all the plantings. The avenues with the Pohutukawa have grown to soften the whole look and feel [of the suburb].”

Start your property search

It’s a story often repeated in Auckland’s more intensified brownfields subdivisions. When David Allen met his wife Maria Tottie decided to downsize, they looked first at central city apartments. When Tottie suggested they take a trip to the show homes at Hobsonville Point, 4.5km from where they were living at the time, Allen wasn’t impressed.

“I said, ‘It’s going to be nappy valley. It’s going to be disastrous.’” But that’s exactly where they moved. To one of the very first homes built in the suburb by GJ Gardner Homes on the former air force base. “Hobsonville Point was literally rabbits and razor wire [in 2012],” Allen says.

Way of the future? Terrace housing in Hobsonville Point in West Auckland. Photo / New Zealand Herald

“We came here to look, and we said, ‘Double glazed, grey water tank, it's a four bedroom detached house, it has a tandem garage.’ There was nothing we didn't like.”

Another positive they realised over time was the compulsory design guidelines that ensure the homes in the suburb are consistent, although not identical. The covenants are a bonus as well, he says.

Buyers often don’t think of the benefits of the covenants at Hobsonville Point, says Allen. They just want to buy a home. But the covenants keeps standards up. “Without the covenants it would get untidy or tatty.”

Allen appreciates the master planning that went into the suburb. It means there are doctors’ surgeries, cafes, dairies, supermarkets and other facilities within walking distance, including a popular market.

In fact, Allen loved his new suburb so much he would eventually become chair of the Hobsonville Point Residents Society (HPRS). The HPRS plays an important role maintaining the standards set in the master plan for Hobsonville Point, supporting community projects, and lobbying for residents.

The new housing bill agreed by Labour and National could see up to 105,500 new homes built in the next five to eight years. Photo / Dean Purcell

Large brownfields sites such as Stonefields and Hobsonville aren’t all that common, because the supply of large tracts of light industrial or other used land is limited. Kāinga Ora is in the process of building a number of new developments in erstwhile state home suburbs such as Northcote and Mt Roskill. Another project at Vinegar Lane in Ponsonby on the old DYC vinegar factory site has been built in recent years. https://isthmus.co.nz/project/vinegar-lane/ Fletcher Living is currently developing the old Winstone quarry at Three Kings, into another master planned community.

The advantage of brownfields sites is often that they’re development ready. There is already infrastructure, presuming that it has capacity to take a more intensive development. A greenfields farm on the other hand is not development ready. It’s also likely to be more remote from the centre.

The other type of brownfield housing within the city limits is simple infill housing is where individual sites are intensified. Auckland is in at least its third generation of infill. The first was the mass appearance of brick and tile sausage blocks across the city in the 1960s and 1970s. Hundreds of these blocks, also called Franchi & Ion units after the building company behind many, are found across the country. Starting around the same time and culminating in the early 1980s cross leasing became popular. That involved a second home being built on the same piece of land. The original section was cross leased so that each owner owned a share.

According to Auckland Council of all new dwellings consented, 82% are within the existing urban area and around two-thirds (62%) are for higher-density housing, such as apartments and townhouses.

Infill housing can often give the community a facelift when well designed by replacing old, dilapidated homes with fresh and new. The Resource Management (Enabling Housing Supply and Other Matters) Amendment Bill announced jointly by Labour and National creates new standards for development in Auckland from August 2022, and is expected to accelerate the movement.

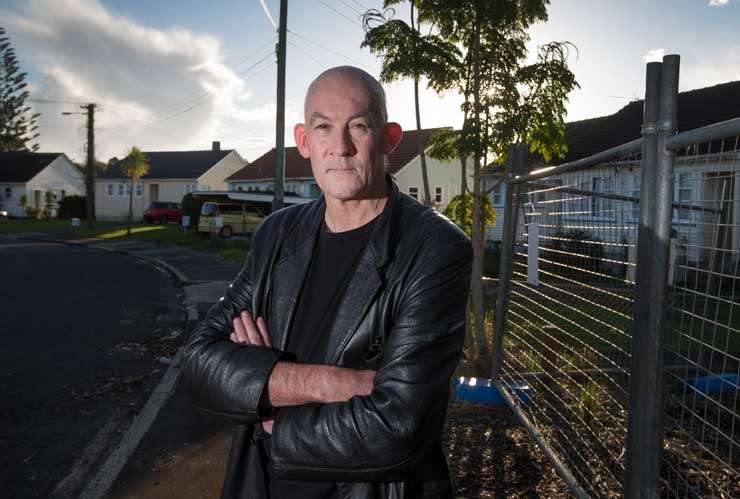

Academic Bill McKay: “I think we need something radical, and we need to get thoroughly dirty.” Photo / Nick Reed

The bill aims to increase the supply of new homes in New Zealand’s major cities by allowing up to three houses, three storeys tall, to be built on most sites without the need for resource consent.

Bill McKay, senior lecturer in architecture and planning at the University of Auckland is in favour of the new intensive building. “I think we need something radical, and we need to get thoroughly dirty for a while. I reckon 20% of that might be shit but the others will actually free homeowners, builders and developers from a lot of red tape.”

That infill housing brings with it diversity of accommodation options. “We’ve got heaps of suburbs. If you really want to live in the suburbs with space to kick a ball around in the back yard, you’ll find something. We need more diversity of options so that the empty nesters will get the hell out of the suburbs and free up housing.” New apartments and terrace houses on brownfields sites allow those empty nesters to stay local but downsize.

New Zealanders do need to be more open to different styles of living, says McKay. “I often say to people that you can’t judge an apartment or townhouse in the same way that you judge a house. They are different animals.”

People adjust and often find to their surprise that they quite enjoy the new style of living, although stairs for people not used to them and the lack of parking, and sometimes increased noise, does take getting used to.

“What's good about them as they're the most compact, which generally might make some more affordable, because you've got less of a footprint and there are more dwellings on the land. They’re generally on or close to public transport routes. All the infrastructure is already there. You have shops and supermarkets (and schools).

“It’s more sustainable in the big picture of an urban footprint than building more and more suburbs miles away from anywhere where people want to live.”