Eye-popping inflation figures have meant the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) has had to act to tame rising prices by raising interest rates.

On the surface rising interest rates are a blow for home-buyers and a welcome relief for savers – especially those who live off term deposits. But the underlying picture is more complex, say economists. And it’s not the RBNZ’s role to favour borrowers or savers.

Commentators predict the RBNZ will raise interest rates further this year. It’s the extent to which that happens that will determine if borrowers, who tend to be younger, or savers, who are often older, are the winners or losers.

The RBNZ’s mandate is to keep inflation under control, which means within 1% and 3%, but ideally closer to 2%. Inflation ballooned to 4.9% in the three months from July to September, which resulted in the RBNZ raising interest rates for the first time since 2014.

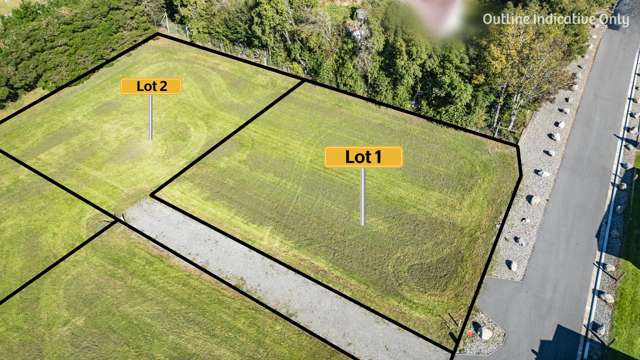

Start your property search

That means borrowers paying more, and savers earning more. But it’s not quite that clear cut, says Associate Professor Dr Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy at the University of Auckland.

“The policy settings that we've pursued over the last few years have favoured the older generations over the younger generations,” says Greenaway-McGrevy. “However, for this particular problem it unclear that it cuts cleanly long generational lines.”

If the RBNZ doesn’t put a lid on inflation it will impact the relative wealth of borrowers and savers, he says. “It's good for borrowers, because the nominal value of their debt will be inflated away. Particularly if wages keep up with inflation. Whereas for savers, they're seeing the purchasing power of their savings erode over time.”

For example, young people aged under 30 who are carrying large sums of student debt, will be quite happy to see that debt fade away thanks to inflation, he says, “provided their wages keep up”.

“Then you have to think about the middle generation. People [who] have bought a home and are paying it off. Obviously, they are better off with inflation that erodes their nominal debt. Again, provided that interest rates aren't too high, and their wages keep up with inflation that can be good thing.

“Finally, the retired generation are probably on balance going to lose from runaway inflation given that many of them are relying on fixed income savings.”

Greenaway-McGrevy says it’s still unclear whether or not rising inflation is transitory or if we’re seeing the beginning of an upwards trend. If inflation continues to rise, the RBNZ will have to raise interest rates again, he says.

Economist Tony Alexander says borrowers, not savers will influence the decisions of the RBNZ. Photo / Fiona Goodall

In theory, he says, if inflation gets out of control, nominal interest rates have to be higher than inflation, both to compensate savers for the erosion of the purchasing power, and reward them on top of that for saving and not consuming.

“If you had a 5% inflation rate, you'd want to see interest rates on deposits closer to 8% to compensate the savers for that 5% loss in purchasing power per year. Plus, the usual reward for being a saver rather than a consumer.”

The worry and the mitigating factor might be concerns over what the property market has done to household balance sheets, he adds. An increase in interest rates that is too large may impact the ability of homeowners to service their mortgage at those higher interest rates. “That's the central tension.”

Independent economist Tony Alexander points out that borrowing and savings rates don’t always rise equally when the RBNZ increases the official cash rate (OCR). “So far, it's gone up more for the borrowers,” says Alexander. “The banks are awash with money, so they don't need to compete aggressively [for savers]. Therefore, savers for the moment are missing out on the policy tightening and expectations of policy tightening.

“That's just the way it goes,” he says. “A lot of that is simply to do with the actions of the [high street] banks as opposed to anything from the Reserve Bank.”

The main impact of monetary policy comes through changes in behaviour by borrowers, not savers, says Alexander. “No central bank is going to try and target the outlook for inflation by concentrating on the savers. It's the borrowers who make the big changes.”

Just what the RBNZ will do is yet to be seen. Twenty years ago, says Greenaway-McGrevy it was easier to predict what it would do to bring inflation back under control. Immediately before the GFC, for example, the RBNZ was largely responsible, through OCR rises, for six-month term deposit rates exceeding 8%. “I doubt we'll return to that kind of regime because there is this concern about how households will cope with the broader impact on the economy will be if interest rates climb too high,” he says.

“And if they don’t do that, it’s a bit of a tell that the property market and household debt is holding a loaded gun to the economy [because] we have let things get out of control to the point where the property market is dictating economic growth.”