- In 2000, the median house price was $170,000; now it’s around $800,000.

- Population growth and insufficient housing development have significantly increased housing unaffordability.

- Experts warn of a “landed gentry” class as housing becomes increasingly out of reach.

A quarter of a century ago, the world was grappling with the threat of the Y2K bug crashing computers as 1999 ticked over to the Year 2000.

Start your property search

That didn’t happen, but in the ensuing 25 years there were deadly earthquakes in Christchurch, a Global Financial Crisis and a global pandemic, to name a few of the big events.

Along the way, the housing market underwent huge change. Back then, few probably foresaw technology allowing people to attend virtual open homes or watch live property auctions on mobile phones.

That’s progress, but the biggest issue most did not see coming was the extent of spiraling housing unaffordability. The consensus among a range of industry experts spoken to by OneRoof was, if you thought housing was expensive 25 years ago, you should see it now.

One economist talked of housing becoming so out of reach the country was in danger of having a landed gentry class.

In 2000, the median sale price for a house was around $170,000 – the median sale price now sits around $800,000.

Wayne Shum, senior research analyst for Valocity, OneRoof’s data partner, says New Zealand was a smaller country 25 years ago and population growth has put pressure on housing and prices.

In 2000, the population was 3.88 million people. Over a million people have been added since then with the population now at 5.3 million people, but the building of housing has not kept up with the need.

Valocity CEO of real estate and former REINZ CEO Helen O'Sullivan says the entry point to the market is much higher now than in 2000. Photo / Fiona Goodall

Global events over 25 years have made building houses harder and pricier, Shum says, who points out that during the GFC of 2007-2009 finance to build was hard to come by.

Helen O’Sullivan, CEO of real estate for Valocity Global, and a former head of the Real Estate institute of New Zealand, says you have to go back to the 1970s for the highest rate of consenting per 1000 residents in New Zealand.

That correlated to a big state housing suburb-building push, but “we have never hit those numbers again”.

O’Sullivan recalls her first interview with RNZ’s Checkpoint programme as REINZ CEO, around 2010, saying Mary Wilson, the host, opened with, “Well, not looking good for the property market is it? Would you be recommending people invest in the property market now?

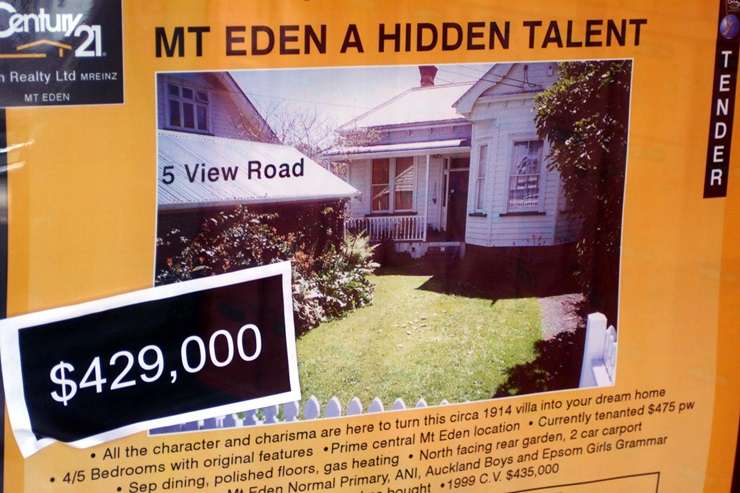

A real estate listing from 2000 highlights the big changes in New Zealand's housing market. Photo / Getty Images

One of the new housing developments that cropped up in Auckland at the turn of the century. Photo / New Zealand Herald

“I probably should have said to Mary Wilson at the time, ‘No, it looks terrible, buy everything you can’.”

O’Sullivan says buyers today face a high entry point into the market, a “dramatic increase” in the proportion of earnings required to service a mortgage, and incomes which have not kept pace with cost growth.

CoreLogic’s head of research Nick Goodall says while interest rates have risen and fallen over the years, with record lows seen after Covid, that’s not the main problem – what has changed, big time, over 25 years is how much more income it takes to pay the mortgage.

In 2000, people spent roughly a third of their income on mortgage repayments but now they spend about half. The figure is currently 48% so has fallen a bit from the 57% peak after Covid, but spending half an income on the mortgage is still hard yakka.

Goodall says the last few years have been the “worst ever” for affordability and the conversation has shifted from “can you get a mortgage?” to “how much are you paid?”

“You have to factor in, can we afford half our income on the mortgage? That’s just the mortgage, let alone all the other expenses – what’s your insurance, what’s your rates, what’s your maintenance, and when you think about the inflation we’ve had to endure. All of those things.”

He says the only way back to paying a third of an income on the mortgage would be for incomes to grow more than house prices for a sustained period, for interest rates to stay low or drop further, and for the construction industry to build 35,000 houses a year.

What went wrong?

None of that is looking likely. Goodall says one of the drivers over the years which has impacted affordability is the development of an unwavering belief by New Zealanders in the safety of property.

That goes back to the 1980s when baby boomers were burnt by the stock market crash and flocked to bricks and mortar to fund their retirements.

The residential property market today is worth around $1.62 trillion – “no other investment class is worth anywhere near that”.

Housing has become complex and a “wicked problem”, says Laurence Murphy, a former property professor at Auckland University’s Business School.

Before the 1990s, Government support for home ownership was strong, resulting in the production of a variety of different types of affordable and entry-level housing.

But in the 1990s, New Zealand radically changed its housing policy with the emergence of a new philosophy that “the market” would provide.

Read more stories from OneRoof’s special report:

- Who are the house price winners and losers of the last 25 years?

- Top economist's housing market scorecard: Which laws and changes get 10/10?

- Ex-minister's overcrowding fears - 15 to 20 people to a house

“If you think about it, in the 1970s, even in the 1980s, the state was the largest provider of mortgage finance in New Zealand, and then it dropped out of that.”

While the Labour Government of the 1980s radically changed the economy, it did not do much to housing, however, the National Government of the 1990s brought in the Housing Restructuring Act, which changed the Government’s relationship with social housing, says Murphy.

The Government sold its mortgage book and shifted towards the retail banks as the main mortgage supply.

Policies followed, allowing the private finance market to fund housing, in line with global trends.

“What we see is the run up to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, so you see a run up of house prices in the USA, the UK, Ireland and Spain, and New Zealand, and that’s really allowing a kind of shift towards large global flows of money into housing markets.”

Some experts believe housing has become more about wealth generation than a place to live. Photo / George Heard

Housing became “less about citizenship and more about investment and making money”.

The result has been winners and losers – those who have been able to make money out of housing, and those who are excluded.

“We’ve created a system whereby we almost ideologically believe the housing market is a money-making machine for individuals, and wealth-generating machine. In doing that we’ve kind of ignored the fact that it’s also a requirement.

“Shelter is a requirement in society, so we need to maybe develop alternative tenures that have different structures.”

Murphy believes the state needs to re-engage and be actively involved in providing housing.

“It sounds like some old political rhetoric, but the role of the state and housing and the provision of housing was really important in the development of home ownership, and the development of social housing and affordable housing, and simply saying we’re going to just support the market creates the wrong incentives.”

‘Inheriting a mess’

The housing minister in the year 2000 was Mark Gosche, a member of Helen Clark’s Labour Government, who told OneRoof he inherited a mess.

The National Government had sold off state houses through the 1990s, and had introduced market rents for state house tenants, who could not afford them and who had to be topped up by way of the “enormously” expensive system of accommodation supplements.

This was part of the Bolger Government’s benefit cuts regime, says Gosche, and a move away from the previous consensus between political parties there be income-related rents for the most needy.

He says “the market” has never delivered for low-income people and as minister he reinstated income-related rents.

“The big intervention in that first three years was stopping the sale of state housing, bringing in income-related rents and starting to build houses again, which was really important.”

Gosche, who resigned as chair of Kainga Ora early last year, says it “beggars belief” the Coalition Government is pulling back from state housing once again.

“Maybe the ministers that are there at the moment are too young to remember the 1990s, but this is the 1990s on steroids.”

Ex-housing Mark Gosche fears New Zealand will suffer a return to the overcrowding of the 1990s. Photo / Jason Oxenham

Affordable housing, be it state provided or private, is vital because without it costs are transferred to other areas, like education and the health system. Gosche says he fears a return to overcrowding issues, such as the meningitis epidemic of 2000.

Economist Gareth Kiernan had just started at Infometrics 25 years ago – he’s a director and their chief forecaster now – and says while hard to believe, in those days housing was seen as a bit over-valued.

But house prices have gone ahead in such leaps and bounds, no one could have predicted or comprehended it.

Structurally lower interest rates flowed into what people were willing and able to pay, and governments threw the country’s doors open at different times resulting in waves of strong migration, so population growth put pressure on housing, especially in Auckland.

Kiernan says it could be argued John Key’s National Government, from 2008 to 2016, felt the easiest way to achieve economic growth was by having more people in the country, but the effect on housing and infrastructure was not given much thought, and over time affordability has “significantly” worsened.

“Sometimes it’s easy to lose sight of that when you look at it every week, or every month, and you go, ‘yeah, I know it’s more expensive than it used to be’.”

He remembers presenting to clients around 2007 and 2008 on house prices, especially in Auckland, “and going, well, these affordability metrics can’t get any worse than this, can they?”

But with the GFC, and the Covid price boom, prices have “been stretched and stretched and stretched far beyond anything that we could have envisaged”.

Economist Gareth Kiernan believes housing affordability has “significantly” worsened. Photo / John Stone

Kiernan was not up for making predictions about what house prices might do over the next 25 years but said he hoped they would not increase anywhere near as fast as the last 25, saying one of the only ways to get into the market these days was by way of property-owning parents who could help out, “sort of perpetuating almost a bit of a landed gentry”.

Rodney Dickens, a former commercial and investment banking economist, agrees affordability is the big story of the quarter century.

Dickens, who now runs Strategic Risk Analysis, says New Zealand has gone from a “reasonably affordable” housing market to one of the least affordable in the world.

Overhauls and tweaks in regulations and policies over the years have pushed up costs, or limited land development, and successive governments have tried different ways to address issues, such as Labour’s failed KiwiBuild policy.

There is no easy fix to a complex issue that has ticked away over the years, says Dickens – “it wasn’t like suddenly one year you went ‘oops’.”

Like others, Dickens is concerned the country is now in a situation where future generations will struggle to afford housing, but he warns pricing younger generations out of housing, or forcing them to take longer to buy, has consequences.

Those young people will have less equity when they retire, which impacts superannuation costs for governments: “It’s a major intergenerational issue.”

Must do better

Another economist spoken to by OneRoof worked out a scorecard of achievements over the last 25 years, allocating the odd high score among very poor ones.

David Norman, formerly the chief economist of Auckland Council, is now with GHD. He worked out his scores according to demand and supply issues.

The foreign buyer ban, brought in by Labour in 2018, gets a 10 out of 10, because when there’s a housing affordability problem people who live in the country need to be prioritised, but Norman gives Labour’s removal of interest deductibility for landlords (now reversed by the Coalition) a zero out of 10, saying that policy reduces demand for investment properties.

He gives another 0/10 to all governments of the past 25 years for not having a population and migration strategy, and is critical of successive governments using population growth as a quick way to boost GDP without considering infrastructure needs.

Economist David Norman thinks there have been some successes from the last 25 years, singling out the foreign buyer as a good piece of legislation. Photo / Supplied

Productivity in the construction sector gets a “really poor” two out of 10. Among issues is no national register of approved products, meaning 70 councils individually determine whether a product can be used.

“What an unbelievably inefficient way to drive innovation in the construction sector and better pricing and, therefore, better affordability.”

Council zoning also scores low, with the exception of Auckland, which introduced the Unitary Plan in 2016 allowing for intensification near jobs, amenities and public transport, and Norman also gives some leeway to Wellington which of late has pushed back against nimbyism.

Current Housing Minister Chris Bishop gets a thumbs up for saying the Government will force councils to open up 30 years of development capacity. If that eventuates it’s worth a nine out of 10, he says.

Norman also recommends changes to how rates are apportioned (that should be based on land value, not capital value), and urges changes to liability rules, which left councils largely holding the baby for the leaky homes crisis which plagued the 1990s/2000s and which is still being felt.

What the real estate agents think

An enduring memory for Remuera agent Steve Koerber is the suffering of unsuspecting owners of leaky homes.

Twenty-five years ago, the real estate industry was not regulated but that has changed for the better. Koerber says the Real Estate Authority has done a great job safeguarding buyers and sellers since its formation in 2009.

Agents these days ask “a million” questions of homeowners around leaks and what’s going on behind walls.

But Koerber also says compliance and anti-money laundering rules have arguably doubled the administrative load on agents, making it harder to operate as a single salesperson without an assistant.

Peter Thompson, managing director of Auckland-based Barfoot & Thompson, has seen his company’s average sale price rocket from just over $300,000 25 years ago to over $1m today, and says average rents have risen from $275 a week to $691 a week.

Barfoot & Thompson managing director Peter Thompson says agents have to be well informed and multi-skilled. Photo / Supplied

Another big change has been the rise of the Internet and the mobile phone, but while the way people search for property has changed, the need for the personal touch from agents has not, and agents today have to be up with everything.

“In fact, they need to be a lawyer, builder, and real estate agent all combined into one as they are having to know the legislation, the type of building material etcetera, and so much more compliance.”

John Bayley, founder of Bayleys in the 1970s, put rising unaffordability largely down to the increased cost of building, saying over the last 25 years the country has not done enough to boost innovation and productivity, or the construction sector, to help get costs lower and to get better quality.

What needs to happen?

One of the calls from some OneRoof spoke to was for more agreement between the different political parties and less chopping and changing of each other’s policies.

Says Goodall: “We do need some cross-party agreement here for some long-term planning. There’s a constant sort of starting-over-process instead of actually getting-anywhere-process.”

A cross-party housing accord for more density was announced in 2021, when Labour was in power, but did not last long.

Norman says the agreement – signed by Megan Woods for Labour and Nicola Willis and Judith Collins for National – was one of the happiest days of his life.

When National reneged on the agreement a short time later, Norman was “similarly devastated”. Had the agreement stood, he would have scored it 10 out of 10.

- Click here to find properties for sale