When it comes to the infrastructure problem plaguing the country, the million-dollar question has fast become a three-hundred-billion-dollar question, because that’s about how much it will take to fix, says David Norman.

Formerly the chief economist for Auckland Council, Norman now works for global engineering, design and construction company GHD.

He has been looking into the infrastructure gap facing New Zealand and says the act of building a house is only one part of a very big and broken picture, although there are a few peeps of optimism.

When a house is built water pipes have to be in place, he explains, so the taps run and the toilets flush, and the transport system has to be in place to get people from their home to their job and back again.

Start your property search

Read more:

- Tony Alexander: Recession haunts the housing market as job loss fears take their toll

- Better and cheaper? Why the cost of buying a new home could be about to shrink

- 'Broke $9m': Christchurch house price record smashed for second time in a matter of weeks

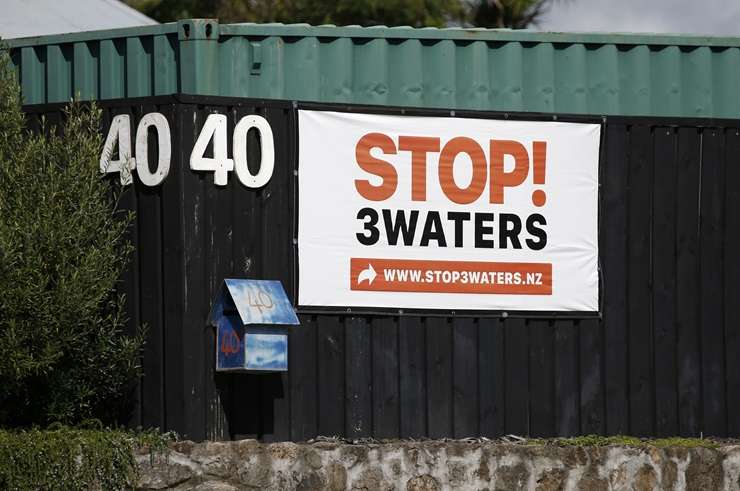

But water is one area emblematic of broken infrastructure. The previous government put in work on this and Norman says whether people agree with Three Waters or not, water is the first sector to reveal a sense of scale around what is needed, requiring an estimated $120 billion to $185 billion to fix over 30 years.

The Three Waters debate has been helpful because it has got the conversation going but other categories need the same conversation, such as transport and energy – energy alone could need $50b worth of investment, he says.

Then there’s the broken health care system, which is “imploding”.

“Sure, part of that is lack of skilled people but we are also operating out of hospitals that almost without exception are approaching the end of their lives, with the exception obviously of Christchurch and perhaps Wellington.”

Schools are another area, so the “frightening reality” is New Zealand is fighting on all fronts at the same time, and the fight is being reflected in the huge rates increases being proposed at local government level.

Norman says there are four main reasons why the country has got to this point and the first goes back decades with local governments failing to depreciate assets – a lot were guilty of this.

Chief economist for building giant GHD David Norman blames current woes on “national short-sightedness”. Photo / Supplied

“It varied from some councils doing it really well to others not doing it at all. When you build something you know you're going to have to replace it one day.

“If you're not putting aside money to replace it, then when the day comes you don't have the money, so there's that failure and that was completely within our control and yet we were careless.”

Norman won’t pinpoint any particular generation as being at fault, saying he blames a “national short-sightedness”.

Reason number two is no one’s fault in particular because times change and so do people’s expectations for an asset, and government legislation changes.

That means even when diligence was put around depreciation 40 years ago, when it comes time to rebuild there is new criteria around what the facility should be.

Take wastewater. Norman says 40 years ago wastewater was discharged into water but now the preference is to discharge to land, meaning hectares of land have to be bought for the replacement facility and a $100m budget may have ballooned to $400m.

An anti-Three Waters sign posted in the run up to last year's election. Photo / Mike Dinsdale

“The public doesn’t like the idea perhaps of discharges going into the water, even if the water is really clean when it does and is up to modern standards, so there is a massive cost implication.”

Reason three is “wild growth”. New Zealand is in the middle of an unsustainably high level of population growth, driven by migration.

Norman says migration has been the central plank of economic policy for both National and Labour-led governments for the last 20 years but the county has not allowed for the growth.

He says he’s not pointing the finger but says migration is an easy way to get headline GDP up and to bring in both skilled and unskilled labour, “which effectively has been a subsidy to businesses but with an infrastructure burden born by all of us”.

Reason four is the reluctance at local government level to ensure growth pays for itself in terms of infrastructure, meaning for decades and decades infrastructure has been provided at a fraction of its true cost to growth, he says.

The windfall has gone to landowners who have gained from infrastructure which has been put in place to build housing or commercial property while the cost of developing the land has been paid for by ratepayers, not the developers.

Increased migration can be a boon to the economy but it also puts increased pressure on infrastructure. Photo / Alex Burton

Historically in Auckland, for example, the true cost of infrastructure for new development was three or four times more than what developers were paying through development contributions, he says.

But Auckland Council has started to get this right, such as by increasing contributions in the development of Drury, and Hamilton has been doing a lot of work in the area as well, Norman says.

“As soon as councils start to signal, as Auckland and Hamilton are now, that development will pay its own way, it starts to send the right signals to the market."

Most of the country, however, lags massively behind “and that means with each passing year [we're] digging ourselves into more of a hole.”

Norman won’t be drawn on whether the Coalition Government is headed in the right direction but does say New Zealand desperately needs a bipartisan pipeline of infrastructure projects of national significance which everyone can agree on to provide certainty ahead.

Multibillion dollar projects need to be lined up so there is a clear pathway, “and then let's get on and actually do it”.

- Click here to find properties for sale