The Covid era has seen house prices go through the roof - but they were rising anyway.

Despite all the noise about price hikes over recent years, and despite measures by the Reserve Bank and both National and Labour governments to rein prices in, they have rocketed from a 2.3 per cent value rise in 2011 to a 27.8 per cent one this year.

There have been loan-to-value ratios (LVRs, which affect borrowing), Brightline tests (a tax on gains), high density-enabled plans for Auckland, a building boom, a nationwide foreign buyer ban, a failed KiwiBuild scheme and tax changes targeting property investors/speculators – yet through it all, prices have marched on, reaching spectacular heights since Covid arrived.

Just last month, Reserve Bank governor Adrian Orr issued a warning house prices are unsustainable, saying they pose a threat to financial stability and telling the Property Council there is no silver bullet.

Start your property search

“House prices and housing affordability are affected by both supply and demand factors, ranging across immigration, tax policy, government benefits or transfers, land availability, building standards, infrastructure and training programmes.”

But access to land and space remained the biggest challenge to ensuring a smooth functioning housing market, he said.

Housing Minister Megan Woods points to “decades of inaction” leading to a severe housing shortfall, saying multiple interventions are needed to increase new development, particularly for affordable homes.

It’s true the past decade can’t be looked at in isolation. Key themes emerged, including a decades-long period of lower interest rates, not enough houses being built, and population growth and migration inflows all impacting housing. There has also been the emergence of a new property investor class the country didn’t have 30 years ago.

The last 10 years

By 2011, housing unaffordability was gaining traction as a real thing but back then more people were leaving the country than coming in.

The market was fairly quiet and few new homes were being built. Kelvin Davidson, chief economist at property data firm CoreLogic, says this post-GFC period was a time when construction confidence was shaken, and we are still dealing with the housing shortages from then.

By 2013, however, sales and prices were rising and net migration went from negative to positive.

Former Housing Minister Dr Nick Smith told OneRoof John Key’s National Government at the time “jumped for joy” when migration turned around.

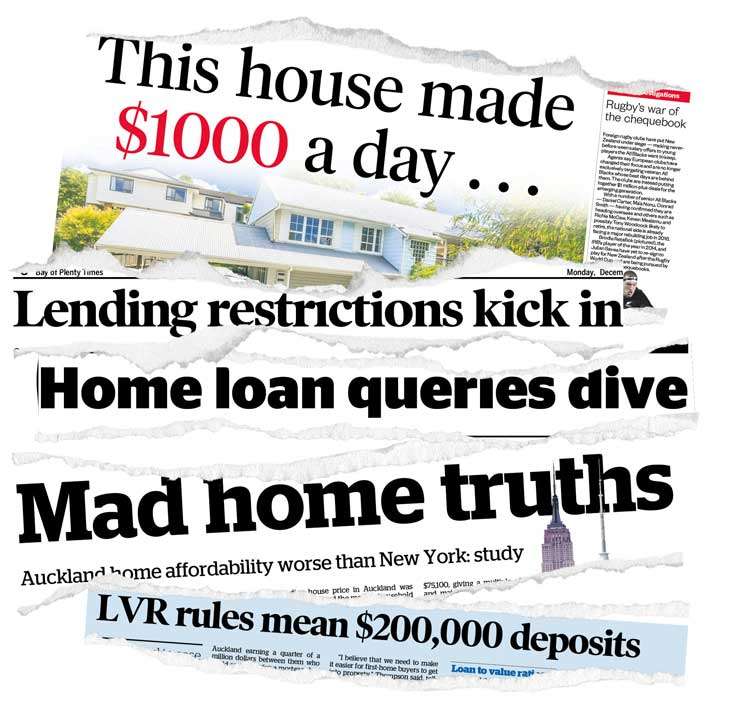

News headlines from the last 10 years show housing affordability has always been front of mind. Montage / Beth Walsh

A big move from Key was to reverse a brain drain that had seen a consistent loss of 40,000 to 50,000 Kiwis to other countries for the preceding 20 years.

“When it turned in 2010 and 2011 we were surprised how dramatically it did so. We didn't recognise quickly enough how much it was going to flow on to demands on housing,” Smith said.

A National Party insider from the time, who did not want to be named, conceded the infrastructure wasn’t there to cope with the incomers – not foreigners but the return home of so many Kiwis.

In 2013, the Reserve Bank, with National Government support, introduced LVRs to target investors but they still remained active throughout 2014 – Davidson says the LVRs made it hard for first home buyers instead.

The next year, 2015, saw strong sales and prices. Mortgage rates headed down while net migration went up, to 59,809.

Investors were still active so National introduced the Brightline test to put off speculators.

By 2017, investors were pulling back and sales and prices slowed. Jacinda Ardern’s Labour Government was elected, partly after campaigning to build 100,000 new homes over 10 years – the KiwiBuild scheme.

Over the next couple of years there were changes to the LVR and the Brightline test. The Foreign Buyer Ban was brought in after fears foreigners, and the Chinese in particular, were buying up all the houses.

Reserve Bank of New Zealand governor Adrian Orr appears before Parliament earlier this year. Orr has warned that current house price levels are unsustainable. Photo / Getty Images

In 2019, the LVR rules were loosened again, and net migration surged to 72,587, putting more pressure on housing stock.

A tax ring fence for rental property losses was introduced, and last year, when Covid hit, a raft of measures were put in place to keep the economy from collapse so people didn’t lose their homes and incomes – measures such as quantitative easing (described often as the printing of money), mortgage deferral schemes, funding for lending and the removal of LVRs.

But house prices boomed higher than ever before. They are still booming now, if a little slower.

The build-up

When the share market crashed in 1987, New Zealand was particularly hard hit. Some people lost their savings. Some lost their farms.

Fearful of shares, they turned to property – and they were encouraged to do so.

Around that time there were fears the New Zealand Superannuation would not survive – the 1990s saw the retirement age rise from 60 to 65.

Housing researcher Kay Saville-Smith calls the buying frenzy “superannuation panic”. She says it was a bit like the panic buying we’ve seen recently with first-home buyers.

Over time, she says, the so-called “mum and dad” investor has given way to a new class of property investor. Her research shows that between 1986 and 2018 there was a 191 per cent increase in the number of property investors, as opposed to people buying an extra property for their retirement. Her belief is that after the share market crash many commercial players switched into residential.

A sold sign outside a home in the Wellington suburb of Churton Park at the end of last year. The capital's average property value is now more than $1m. Photo / Getty Images

Compounding that was the “Mother of All Budgets” in 1991, from the Bolger government, when market rents were introduced for state house tenants.

That’s important, Saville-Smith says, because a signal was given to private investors there would be an accommodation supplement available to assist people in private rentals, and that opened up a lucrative market for them.

“The failure to take that into account and really take that seriously I think is a failure of the Reserve Bank. It’s also a failure in other government agencies that have an interest in there.”

Other factors have been at work, too. Saville-Smith also cites high migration, which she’s not against, it’s just that it wasn’t planned for - and that’s because the tools to plan for it were “got rid of” in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Before that, governments had the Housing Commission, for example, which wrote reports on who was coming in and what they needed, but that stopped three decades ago.

Back then, she says, housing wasn’t seen as a problem. New Zealand had done well with low-cost lending and families could use the defunct family benefit for deposits. There were also low levels of homelessness.

But in the 1990s the funding fuelling the building of low-cost housing was removed so builders turned to constructing more expensive homes.

Other things, too, like covenants which prevent low-cost building in subdivisions, affect prices – in 2017 around half of all new titles were covenanted, Saville-Smith says.

There may be more terraced homes now, and they’re often cheaper than standalone houses, but that still doesn’t make them affordable, she says.

The economists

Tony Alexander has watched the housing market for years – he was the BNZ’s chief economist for nearly 25 years and continues to analyse the market as an independent economist.

Measures like the Brightline test have minimal impact on prices, he says, though LVRs have had some restraining impact and are a useful tool.

The main reason prices have risen is because over the last 30 years interest rates have fallen.

“Factors in favour of house prices rising have simply been way too powerful for any sort of reasonable political policy to have had much of an impact, quite frankly.”

In 1987, interest rates were up in the 20s and the Reserve Bank was fighting inflation.

When the share market crashed it eventually caused weakness in the economy and interest rates came down.

Tony Alexander says the impact of the Brightline test on house prices has been minimal. Photo / Fiona Goodall

Combined with that, governments ran campaigns to get people prepared for their retirement and housing became a portfolio investment class of its own.

That’s reflected in the home ownership rate, which has fallen to around 62.5 per cent from its peak of around 72 per cent around 30 years ago, he says.

“If New Zealand governments had wanted to stop the sharp increase in the ratio of house price versus incomes, I think they would have had to actively prevent housing from becoming a more popular retirement asset.”

Other factors, like the trend to buy bigger homes, have also affected prices because bigger homes are more expensive. Also, anti-urban sprawl planners wanted to restrict the availability of land.

Sharon Zollner, ANZ’s chief economist, pinpoints the Reserve Bank Act of 1989 as the place to start.

The Act gave an inflation target and the result was lower nominal interest rates and a much lower inflation environment, which means people can service a lot more debt.

Instead of only being able to borrow two or three times their income, they can borrow six or seven times. If you can borrow more, you can pay more – “it’s just maths”.

While the change to the inflation environment has been good for price stability, the extent to which house prices have risen has been an unintended consequence.

That house prices have risen way more than inflation comes down to supply and demand, Zollner says, another key factor in the picture.

“Fundamental housing demand depends very much on how many people you’ve got in the country and that’s increased a lot – our population growth rate has been really high.”

Unaffordable Auckland

For the last 17 years, Auckland has consistently featured as one of the most unaffordable cities globally in the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey.

Hugh Pavletich, who lives in Christchurch and who co-authors the surveys, says it’s an “obscenity” the average property value in New Zealand has reached $1m, according to the OneRoof-Valocity House Value Index.

ANZ chief economist Sharon Zollner: “Our population growth rate has been really high.” Photo / Dean Purcell

It takes around nine times the average income to buy a house in this country and in Auckland the figure is 11 – but it shouldn’t be more than three, Pavletich says.

He puts the blame squarely on the lack of land supply and the inappropriate way infrastructure has been financed.

“I’ve been like a scratched record on this. I’ve been so boring for the last 18 years that if boringness was a crime I would have been jailed a long time ago.”

New Zealand needs to learn from the United States, which bond finances its infrastructure. While the Government passed the Infrastructrure Funding and Financing Act last year, which had cross party support, passing a law is one thing and making it work another, he says.

Successive governments have failed to solve the housing and infrastructure problem, although Pavletich praises former National Party Finance Minister Bill English and former Reserve Bank Governor Graeme Wheeler for getting the Productivity Commission to produce a report on housing affordability.

The median house price had increased over 50 per cent between 2004 and 2008 and the report, released in 2012 and written by Dr David Law, found it was increasingly difficult to afford a house.

Dr Law, who is now with the New Zealand Initiative, says governments have tended to focus on the demand side of the equation, with measures like LVRs and Brightline tests, when the real problem has been supply and demand.

Each has made promises they haven’t kept, whether it was Labour’s KiwiBuild (a “complete disaster”) or National’s promise to reform the RMA (which he says they didn’t do).

Crowds outside an Auckland real estate office earlier this year The city’s average property value is just over $1.5m. Photo / Getty Images

Now, the Labour Government’s promised reform of the RMA could make the whole thing worse: “They’re going to make three Acts instead of one, so it’s going to get more complicated to understand.”

If previous governments had acted better and faster, the Covid-related price surges might not have been so bad: “If we’d had flexible supply to adjust to all the demand, we wouldn’t have seen this.”

The ongoing debate around housing is a frustrating one, he says.

“We’ve been saying ‘Oh God, house prices are going out of control’ for probably the better part of 15 or 20 years and we’re just kind of tinkering all the time.”

The National Party

A National Party insider from the Key Government pointed out some of the challenges being faced around housing after the 2008 election.

Back then, the idea that supply had an influence on house prices was ridiculed.

That might seem hard to believe, as supply and demand is widely accepted these days as a driver, but in 2008 housing was barely seen as a proper market, he said.

The insider also pointed out the context of the time – Auckland was becoming a single city, amalgamating the regional council and seven city and district councils, which meant the city’s plans had to be rewritten.

When told it would take nine years to get the Unitary Plan done, National, in “a miracle of administrative bullying”, got it done in three.

Former Housing Minister Nick Smith admits National underestimated levels of net migration. Photo / Getty Images

That process threw up the “weirdness” of the existing regimes around the availability of land, or lack of, for building and redoing the plan was critical in changing that.

“Without that the current situation would be a lot worse, because it opened up large tracts of Auckland,” the insider said.

Many people didn’t like the idea of density back then but it has become much more accepted now. The shape of Auckland is changing with all the building that is going on.

The insider said the earthquakes in Christchurch early last decade also opened eyes around the housing market – enormous funding went into infrastructure and building in Christchurch and valuable lessons were learned.

“For instance, you can build thousands of homes quickly, and that has a restraining effect on house prices.”

That National government went on to establish the Housing Infrastructure Fund and the Local Government Funding Authority, meaning the current Government has a series of infrastructure-related funds it can use, the insider said.

When asked why none of that stopped prices skyrocketing, the insider pointed to the fall in interest rates. “There are models that say the prices are roughly where you would expect them to be, given what’s happened with interest rates over 20 years.”

The ex-Minister

Dr Nick Smith, who took on the housing portfolio, says for the first few years after National was elected there was far greater concern there would be a house price collapse, which happened in other countries after the GFC. He says Housing was the most difficult of all the portfolios he held.

In New Zealand the collapse was in new house construction, which fell to under 10,000 a year.

What was under-estimated was the sharp turnaround in net migration that took place in 2010/2011. It was Kiwis, not foreigners who were buying, says Smith, who is scathing of Labour’s “Chinese-sounding name scandal” a few years later.

“Rather than a net outflow of about 30,000 per year to Australia and further afield it effectively balanced out. As a consequence we started to see those house prices and demand shift in 2011.

“I came into the housing portfolio in 2012 when we were building only 13,000 a year.”

While National “jumped for joy” when Kiwis came home, in hindsight maybe that should have triggered concern about what it would mean for housing supply, he says.

He also says National recognised property investors and speculators were an issue in driving prices too high, which is why LVRs and the Brightline test were introduced under National.

House-building in Auckland. The increase in construction could slow house price growth in the city. Photo / Fiona Goodall

Smith has no regrets and is proud of the work carried out when housing was his portfolio – from introducing the KiwiSaver HomeStart scheme to helping first home buyers with their deposits to fast-tracking the Auckland Unitary Plan.

“The fact that we believe supply was the primary problem and that we grew new home construction from 13,000 homes a year to 31,000 a year is a credible record.”

Housing was by no means solved and still isn’t but “there needs to be an appreciation that, you know, I’m sorry, New Zealand’s housing is now worth over a trillion dollars – it’s a massive sector.”

Back when Smith was taking on the housing portfolio, research economist Arthur Grimes was chairman of the Reserve Bank (from 2003 to 2013).

Now a senior fellow at Motu Economic and Public Policy Research Trust, Grimes has long called for a managed crash in house prices.

When he was chairman of the RBNZ house prices weren’t concentrated on as much as the Consumer Price Index, which includes rents but not house prices, he says. While the Reserve Bank Act is good, in retrospect it probably did not put enough emphasis on house prices.

Having said that, successive governments have failed to curtail rising house unaffordability and under Labour the housing crisis has become a catastrophe, he says.

Both parties turned down introducing a capital gains tax despite tax working groups arguing for one. Grimes says both Key and Ardern were elected on the basis there was a housing crisis yet both administrations have been against prices falling.

He puts those decisions down to “vote greed”, with each administration wanting to win elections.

The outlook

One man who is not gloomy about the future is Hugh Pavletich, the Demographia housing affordability campaigner.

That’s because of the record number of building consents the country is seeing.

He points to StatsNZ data which shows that back in the last big building boom in the 1970s, under Norm Kirk’s Labour government, around 13.4 dwellings per 1,000 people were being built.

If you look at consents now, it’s around 10.4 per 1000 population, and that’s “not a million miles from the Kirk-era peak”.

Selwyn District Council in the South Island is even busier, with around 27 new builds per 1,000 people, which Pavletich describes as “world territory stuff”.

He says New Zealand is building homes at a faster rate even than China, which has been pumping out 10.3 dwellings per 1,000 people.

Prices could come down in New Zealand, he thinks, because things can turn around very quickly.

And politics can change quickly, too. In a rare outing in October, Labour and National joined forces in announcing the Housing Supply Bill, which will allow up to 105,500 new homes to be built in less than 10 years.

That’s welcome news, say both Pavletich and Grimes, with Grimes saying it could contain, or even reduce, house prices over horizons of five to 20 years – but not in the short term.