Every year buyers get knocked back from getting a mortgage. Sometimes the reasons can come as a surprise. That can be anything from the house being too rundown to the person being too old, in the bank’s opinion. Here are 13 of the most common reasons home loan applications are declined.

1. Savings that aren’t genuine

Many young Kiwi rely on the bank of mum and dad for their house deposit. On the other hand, banks want to know that the person they’re lending to is good with money. Most banks require borrowers to have saved at least 5% of the deposit themselves, says Rupert Gough of Mortgage Lab.

2. Too many open lines of credit

Start your property search

Unused lines of credit of any sort can be reason to decline a mortgage. That may be overdrafts, credit cards, car loans, and, increasingly, Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL). What counts to mortgage lenders is the available credit, not how much of it is being used. Anyone turned down for this reason should apply to get their credit reports from reporting agencies Equifax, illion and Centrix, which hold records on most adult Kiwi; then close down unnecessary lines of credit that show up in the report. Utilities accounts are also seen as credit because the goods (electricity, water and phone services) are supplied before the customer pays.

3. Too much consumer debt

Repayments on consumer debt, student debt, and tax debt all reduce the amount of “uncommitted income” a person or couple has to pay on mortgage repayments. Even if the home buyer knows they can afford a mortgage, the Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Act (CCCFA) requires banks to lend responsibly within strict criteria. The straitjacket of the CCCFA doesn’t allow the bank to lend to such people, says Geoff Bawden, mortgage adviser at Bawden Consulting.

4. High risk credit history

The credit reporting agencies use a variety of data to provide a score on individuals. Banking, borrowing and spending behaviour viewed as risky can lead banks to decline mortgages. Defaults (which are $120 payments later than 90 days outstanding) remain on individuals’ credit reports for five years. Beware that every time a person applies for credit, even if they don’t take it out, the application shows up on a credit file. Too many credit-related applications could suggest the person is in financial stress and therefore not a good bet for paying a mortgage.

Make sure you pay your bills on time. Photo / Getty Images

5. A habit of late payment

In recent months Loan Market mortgage adviser Lisa Meredith has seen a trend emerging where banks decline mortgages on so-called “positive” data held by credit reporting agencies. This is data that shows the pattern of payment on credit accounts such as utility bills and loans. The person may not be building up defaults; they’re just not paying bills on time. In this scenario the bank may tell the borrower to turnover a new leaf and come back in three months time. “The other one is unarranged overdrafts,” says Meredith. “If you go over your overdraft limit, even just once a month, or miss a bill payment before your salary lands in your account, that can stop [mortgage] lending. We have to go back to the client and say ‘go on a bank account diet because you need three months of clean banking’, before we can resubmit the mortgage application.”

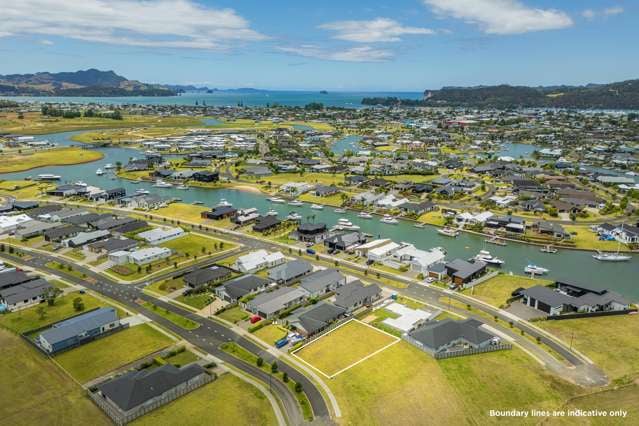

6. Location or property type

Banks may be hesitant to lend on properties because of their location, such as in a flood zone. Sometimes certain types of properties such as leasehold homes or tiny apartments can be difficult to borrow against.

7. Unconsented works

Banks will check listings and Land Information Memoranda (LIMs) and if they find unconsented works they often won’t lend, says Meredith. “If you’re one of the lucky ones to borrow over 80%, then the property has to be what the bank deems to be really saleable.” The reason for this is the bank needs to be able to sell at mortgagee sale if the owner can’t keep up repayments. Unconsented works make that difficult. In particular, unconsented bathrooms, kitchens or additional rooms are a real no-go for banks, she says. So too are unconsented garage conversions. “With an unconsented deck, you might be able to discuss this with the bank.” Each bank has slightly different rules and the decision might come to an individual assessor, says Meredith.

Low deposit buyers will have to show they have the funds available to bring a do-up property up to scratch. Photo / Getty Images

8. DIY projects

It may be as Kiwi as paua and pavlova to buy a complete do-up as a first home. Low deposit buyers are unlikely to be approved by the bank, however. “The [buyer] needs to be able to demonstrate they have a pot of money to pay for the work,” Meredith says. The higher the deposit, the easier it is to get a mortgage on a do-up, or home with unconsented works.

9. Being self-employed

Self-employed people including contractors are often blindsided when the bank says “no”. It’s not that banks specifically dislike self-employed people. It’s just that the self-employed often have good accountants who can make their income vanish miraculously - albeit legally - come tax time. That’s great to slim down the tax bill, but not when a home buyer needs to prove income to get a mortgage. Self-employed people’s banks often look only at their net profit and decline the loan. A mortgage adviser will know how to add back in genuine cash expenses such as home office costs, which increases the borrower’s income on paper. When banks run the numbers on a self-employed person they typically look at the average of the last two years’ income. If the self-employed person has had a bad year financially in one of those two years, it can also be problematic.

10. Probationary employment periods

Home buyers sometimes don’t realise that changing jobs or taking casual work or a contract just before getting a new loan can be problematic. Banks need proof of income. Even if it’s just one member of a couple, the bank may not be willing to advance a mortgage. Probationary periods can be a real problem. One way around this is to ask an employer if they can waive the probationary period after 30 days rather than 90 days, for example.

11. Ageism

Being too close to retirement leads to loans being declined, says Meredith. “It’s becoming very ageist,” she says. Mortgages are generally 25 or 30 years long. Once a borrower turns 50 banks start declining loans based on their age. The argument is that they don’t have 25 years worth of work left in them and won’t be able to pay the mortgage once they hit age 65. That can even include people who only need a few tens of thousands as a top-up on a loan, says Bawden.

12. Unable to get insurance

To get a mortgage, the buyer must be able to get insurance. Karen Stevens, Insurance & Financial Services Ombudsman, says the decision by insurers not to insure someone can be made for a number of reasons including past convictions, claims history, pre-existing damage to the house, recent natural disasters affecting the region, or having insurance cancelled or not renewed for other reasons. Anyone caught committing fraud, even soft fraud that some Kiwi call “white lies”, such as adding a few extra items onto a claim, will have their name added to the insurance industry’s Insurance Claims Register (ICR). Being listed makes it very difficult or even impossible to get insurance because insurers don’t like to offer cover to “any consumer who has made false or incorrect statements, or committed fraud”, says Stevens. Names remain on the database in perpetuity. Home buyers listed on the ICR can’t just insure the property in their partner’s name. If found out, a claim would be declined.

13. Guaranteeing someone else’s loan

Being a guarantor on someone else’s car loan or other lending will result in the third party debt being counted against the home buyer. Someone guaranteeing a $20,000 loan, for example, is considered to have that $20,000 loan themselves when mortgages are calculated, says Meredith. “The bank attributes the entire debt to you [the guarantor].” That’s because in a worst case scenario, the guarantor would have to pay that guaranteed money back if the person who borrowed it subsequently defaulted. Meredith has even seen this affect a buyer who was a trustee on the parents’ property. The bank counted all the debt on the parents property against the trustee.