Restrictions on how much people can borrow to buy a house relative to their income could be a significant game-changer for the housing market, says Kelvin Davidson, chief economist for CoreLogic.

The Reserve Bank has signalled Debt to Income (DTI) restrictions could be imposed through banks in early 2024.

In a statement in November, when the bank was consulting on the framework for DTIs, it said DTIs could help support financial stability and sustainable house prices by reducing the risk of boom-bust credit cycles that amplify downturns in the real economy.

“They complement loan-to-value restrictions on mortgage lending, another macroprudential tool the Reserve Bank has been using in recent years,” said the statement.

Start your property search

Davidson says it looks likely the bank will impose DTIs at a cap of seven times someone’s income, be they owner-occupier or investor, although with exemptions for new builds.

It might be wise for some people to buy ahead of the changes, he says, because come 2024 borrowing at eight times or more your income could be difficult.

The change is likely to hamper investors the most because they borrow at higher DTIs more often.

“If you earn $100,000 and the cap is set at seven basically you can have $700,000 of debt.

“Now, if you’ve got a mortgage against your own property of $400,000 then you can only have another $300,000 – that’s not going to go very far in terms of buying another property so it will be quite a biting restraint, I think.”

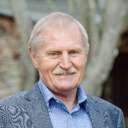

CoreLogic chief economist Kelvin Davidson: “It does restrict how much debt you can have so it's kind of dampening the next upswing.” Photo / Peter Meecham

A DTI of seven would cap how many properties someone can own, says Davidson, who says a comfortable DTI to service a mortgage is subjective but that the Reserve Bank appears to have settled on six to seven as being the threshold.

While a higher DTI makes it harder to service a mortgage, a lower cap of perhaps five might not net the house someone wants.

“If you think about a household income average across the country of $110,000, $120,000, if you borrowed at a ‘comfortable’ DTI of five, then really you're only getting $600,000 of mortgage.

“You top that up with your 20% deposit you can buy a property for $700,000, $750,000 which is giving you something but it's maybe not exactly what you want.”

Davidson says the economic rationale for DTIs is about long-run housing affordability.

“It does restrict how much debt you can have so it's kind of dampening the cycle, dampening the next upswing.

“They're trying to remove, or lower the chances, that we see another post COVID 40% rise in the space of a couple of years.”

Because the mechanics of DTIs means borrowing capacity goes up proportionally to someone’s income if that income goes up five per cent they can borrow five per cent more and therefore pay five per cent more for a house.

“You can't really see 20% growth in house prices, or 30% growth in house prices, because it is tightly linked to income growth.”

The Reserve Bank’s headquarters in Wellington. The Reserve Bank said in November that it was consulting on bringing in DTIs. Photo / Getty Images

If DTIs had been in place after Covid arrived in 2020 Davidson says there may not have been such a big growth in house prices because incomes did not grow at the same pace.

“I think it will mark quite a big regulatory shift. I don't think it will necessarily change things overnight when they come in but it's about that longer term dampening the next cycle.”

Michael Gordon, acting chief economist for Westpac, says one of the issues the Reserve Bank has raised is not wanting to set DTIs in a way that is overly restricting for some buyers, particularly first home buyers, but still high enough to have an ongoing restraining effect on the investor market.

“There's a fine balance to be struck there.”

But he says with the fall in house prices since the bank began looking at DTIs it could be possible it locks in a lower threshold.

“They may well be able to lock it in at something that’s more like five if that’s the prevailing lending standards by the time we get into early 2024.”