Anyone who already owns a house is a winner in this past year of extreme house price surges around the country, with the average gain nationwide just over $200,000.

Some areas have done better than others, with central Auckland suburbs enjoying the country’s biggest windfall ($313,000), and homeowners in Waitomo having to make do with a gain of just $44,000.

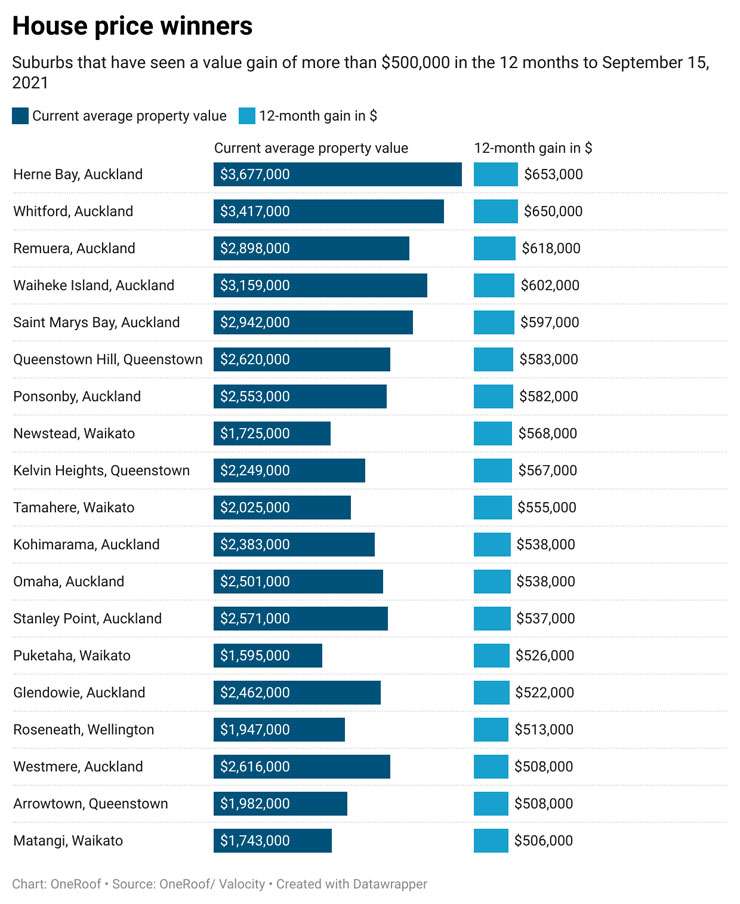

According to OneRoof figures, the suburb that has delivered the most is also New Zealand’s most expensive. Herne Bay’s average property value jumped $653,000 to $3.677m in the year to September 15.

Of the 1000-plus suburbs that saw more than 20 sales in the last 12 months, 19 enjoyed value gains of more than half a million dollars.

Start your property search

Surprisingly, not all are in Auckland. Four - Matangi, Newstead, Puketaha and Tamahere - are in Waikato; three – Arrowtown, Kelvin Heights and Queenstown Hill - are in Queenstown; and one - Roseneath - is in Wellington.

No suburb lost money in the post-Covid boom, but Kaitangata, in Otago, did the least well out of the market surge, with the suburb’s average property value rising just $26,000 to $240,000. That’s less than what Herne Bay earned in a month.

The overall figures are grim for those who haven’t yet been able to break into the market. The $200,000 leap in New Zealand’s average property value to $1 million has put the squeeze on those saving for a deposit.

Miles Workman, senior economist for the ANZ, says young people coming into their 20s face carrying the biggest debt levels relative to income of anyone in living memory if they want to own a home. “From an intergenerational equality perspective it’s quite a sad tale, really,” he says.

If you look at house prices relative to income the pool of people who can afford to buy a house is shrinking, he says.

And when you put some assumptions into the picture around income growth and price inflation for the medium term, with one of those assumptions being house prices don’t fall, some scenarios show a multi-decade path of grimness.

If house prices grew at the historical average of three per cent and incomes grew around four per cent, it would take 39 years for the ratio of house prices relative to incomes to return to pre-crisis levels, Workman says – that’s a couple of generations.

“What it suggests to me is the tailwind in the housing market has been blowing very, very strong and it has been blowing quite strong for the last 30 years.

“We haven’t been building enough houses – that’s the structural, fundamental problem, and then on top of that you get these cyclical drivers such as low interest rates.”

Houses under construction in Wellington. Photo / Getty Images

Young people watching the housing market often respond by saying they are giving up on home ownership, Workman says.

“There's also a cohort that just simply have to save for so much longer just to get that deposit together, and in order to do so it's more likely in this day and age to require two incomes to service the debt, and they are getting into a debt position relative to their income that is much higher than anyone in living memory has really had to deal with.”

Single people on a median wage will find it exceedingly tough to save to own a home, he says.

In one scenario Workman took 30 per cent house inflation and a $1m house as his starting point.

After interest costs a homeowner made about $275,000 in unrealised capital gain but someone looking to enter the market who didn’t have the 20 per cent deposit had to save an extra $60,000 just to stand still.

“When you put it into daily numbers the saver needed to find $165 a day and the person who owned the house was making an unrealised capital gain of $750 per day.”

The ANZ is projecting house price inflation will slow markedly over the year ahead, however, and there may even be a couple of negative months as interest rates are expected to rise with the OCR expected to be lifted from October.

A crowded auction room in Wellington at the end of last year. Photo / Getty Images

But if prices did fall that would only be very small, Workman says, and not enough to take the annual pace of inflation into negative territory.

While Auckland is exceptionally unaffordable for a lot of people, the regions have also become unaffordable for many.

Nick Goodall, head of research for CoreLogic, agrees anyone who was able to buy a house in the last year has done pretty well but those who have not been able to due to deposit and/or credit requirements have missed out.

CoreLogic figures show various parts of the country have seen huge price growth, including the Tararua District which has had 52.2 per cent growth. That’s followed by South Wairarapa at 44.9 per cent, Masterton at 42.4 per cent, Grey District at 42.2 per cent and Whanganui at 41.4 per cent.

And while not everywhere experienced such big growth, there was still growth, such as MacKenzie with 7.1 per cent, Southland with 14.1 per cent and Ashburton with 18.3 per cent.

“In terms of why there is a difference, it’s difficult to be too specific, but in a general sense those at the top are concentrated on the lower half of the North Island (except Grey) while those in the bottom are from the lower half of the South Island,” he says.

“This may reflect the prospects of each local economy and/or the general population bases which contribute to housing demand, either buying or renting.

“There may also be a ‘Covid/remote working’ boost for areas that are well connected to larger cities, like Wellington, but more affordable which is contributing to increased demand, and therefore price pressure.”

James Wilson, head of valuation with OneRoof’s data partner Valocity, says while areas like Gisborne, Whanganui and the Hawke's Bay have seen big growth on paper, that growth does not necessarily mean much for many buyers and sellers.

He points out the price hikes seen around the country may be related to the national shortage of listings. “One of the key drivers of that right now is that even people who you might call winners on paper - so their area or property has had massive growth in value – even those people are still potentially blocked out of their next purchase.

“If your value has gone up so has the value of the properties around you.”

To buy a similar property in the same location or take the next step on the ladder means taking out a “heck of a lot” more debt to do that. That means people are instead not moving and therefore not listing their homes. “That's quite a new theme for New Zealand and I think it really has come about because of the rate of that growth in the last 12 months.”

And where in the past people who couldn’t afford central Auckland would buy on the fringe, and if they couldn’t afford that they would buy in the regions, the rapid price growth in regional New Zealand has meant people already living in those areas are finding their local market now priced out of their reach. That becomes a very difficult pill to swallow.”

Brad Olsen, principal economist at Infometrics, says the last 12 months have been a game of two halves with investors active for the first half then owner occupiers for the second, and first home buyers have benefited from the lower interest rates. The difficulty for many has been the struggle around trying to weigh up the different options.

Some sellers have been wanting to collect on some of the gains they have made on paper but they also then ran into the listings shortage.

“You could well be selling at the same time as trying to buy a more expensive house so I think there’s been more hesitation on the sellers than the buyers’ side in many respects,” he says.