Clearly the mortgage lending environment has taken an abrupt turn in the past 3-6 months, from being a driving factor in the wider property market’s upswing to now being a restraint on both sales activity and value growth. What are the key trends and implications?

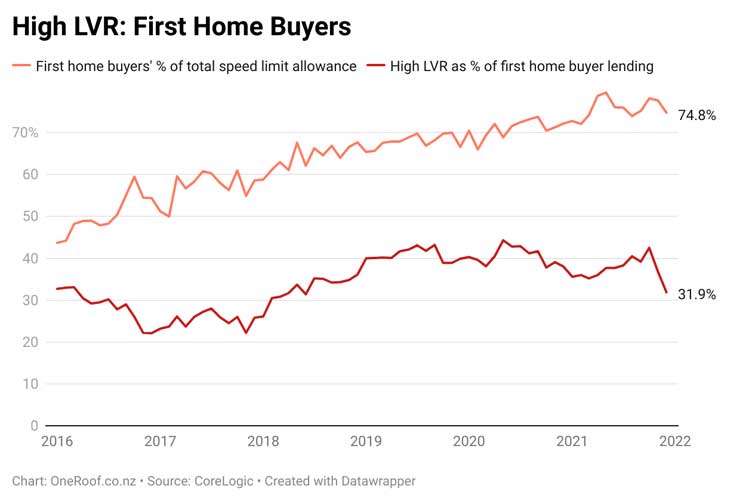

Let’s start by looking at the key regulatory changes. First, it’s the loan to value ratio rules (LVRs). Investors have clearly been facing increased deposit requirements for quite some time now (officially 40% from 1st May last year, although the banks acted much earlier than that), but owner occupiers are now facing tougher restrictions too. In December, only about 9% of loans to owner occupiers were done with less than a 20% deposit, the first foray below the new 10% speed limit that became official on November 1.

But don’t just assume that’s as tough as it gets for owner occupier deposits. In fact, the last time that the speed limit was set at 10%, the banks themselves held the figure down at 5% (or in other words kept a 5% safety buffer), and there’s a good chance that some could go even lower this time around, possibly all the way to 0%. A complete shutdown for low deposit lending would sting first home buyers (FHBs) in particular, as they’ve been the dominant users of the previous allowance.

Start your property search

Second, the December changes to the Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Act (CCCFA). The Government has said it will tweak the legislation following an outcry over its impact. The CCCFA has no doubt shut out several would-be borrowers who may otherwise have got a mortgage. Anecdotally, the CCCFA changes seem to have hit FHBs the hardest, although some early insights from Centrix (the credit risk monitoring firm) on indicators such as credit demand and mortgage approvals suggest that the real impact has perhaps been a bit less than some headlines suggest.

So based on what we’ve noted so far, you’d be forgiven for thinking that housing policymakers are actually trying to hamper FHBs rather than help them. However, investors are not emerging unscathed either. On top of the previous changes to LVRs and the phased removal of interest deductibility, there’s now the looming possibility of a cap on debt to income ratios (DTIs) later in the year, at a figure of perhaps seven. Of course, some banks are already applying DTIs too.

CoreLogic chief economist Kelvin Davidson says the CCCFA changes seem to have hit first home buyers the hardest. Photo / Peter Meecham

On the latest data we have to hand, less than 8% of FHB loans are done at a DTI >7, while for other owner occupiers without investment property collateral the figure is about 13%. But for other owner occupiers with investment property collateral (i.e. those borrowing against a rental property to fund their next home purchase or build), the figure is 35% and for investors it’s 37%. Clearly, these figures suggest that a broad-based DTI system would hit investors the hardest.

As a slight aside, let’s just take a quick look at interest-only lending (something which faced regulation in Australia). This type of loan has escaped the regulatory tightening in NZ so far, even though it’s still popular and potentially viewed by some as ‘risky’, given that there’s no principal being repaid. Recently about 22% of lending flows to owner occupiers has been interest-only and 39% to investors. These figures might still seem high to some, but at least they’ve already come down a lot – back in 2015-16, more than 50% of investor lending was interest-only, with more than 30% to owner occupiers.

Although this type of lending hasn’t been formally restricted, there is likely to be some self-regulation underway on the part of borrowers themselves (and possibly by the retail banks too). After all, with mortgage interest deductibility being phased out, this gives investors an even stronger incentive to get their equity levels up as quickly as possible – or in other words, go with a principal and interest mortgage.

Now, on top of the changes to general credit conditions, you’ve also got to factor in the cost of a mortgage too. And as the official cash rate has started to increase, so too have mortgage rates jumped sharply – whereas a fairly typical one year special fixed rate used to be less than 2.5%, it’s now more than 3.5%, and could well be 4.5% or more by the end of 2022. To illustrate what this means, going from a rate of 2.5% to 4.5% on a standard repayment mortgage over a 30-year term (fortnightly repayments) equates to an extra $1350 in payments every year per $100,000 of debt.

That said, just a small word of warning here; we can’t rule out the possibility that the OCR actually ends up being raised by less than is currently predicted, simply because lower spending in the economy as people divert more money towards the mortgage does a lot of the work of subduing inflation.

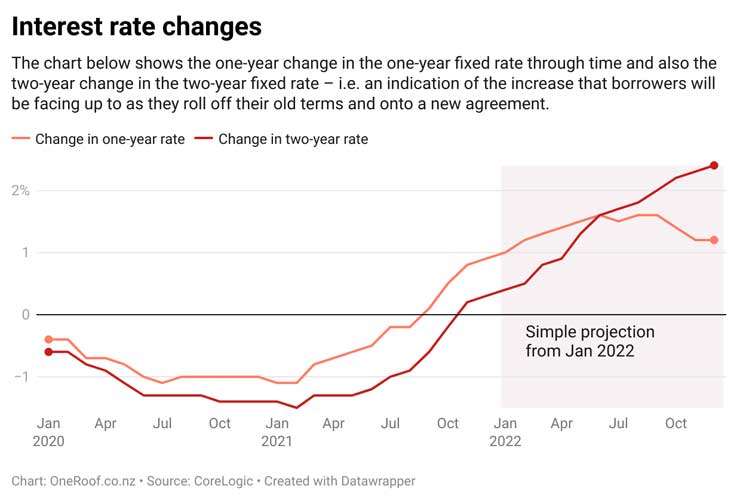

Of course, the bulk of mortgages in NZ are on fixed rates, so this gives some near term protection to the borrower. However, with 11% of loans actually floating and another 54% fixed but due to be refinanced in 2022, this protection from higher mortgage rates won’t last too long. So what sort of change in rates might people be exposed to?

The chart below shows the one-year change in the one-year fixed rate through time and also the two-year change in the two-year fixed rate – i.e. an indication of the increase that borrowers will be facing up to as they roll off their old terms and onto a new agreement. As you can see, the increase could be about 1.5% for anybody refinancing a one-year fix in the middle of the year, before rising towards 2.5% for borrowers rolling off a two-year fix late in 2022.

All that said, you might also ask why there’s even been all the fuss and rule changes. After all, even if the shorter term fixed mortgage rates rise to 4.5% or more this year, that’s still well below the serviceability test rates already being used by the banks (typically reported to be 6.5% or more). In other words, provided people keep their jobs, this suggests that most should be able to adjust their finances without too much undue pain. (On this note, though, we’d also just flag up that we’ll still be watching the unemployment rate closely – any signs that businesses are closing as government support winds down would be an extra headwind for the property market).

In addition, although the Reserve Bank data shows that provisions that the banks have on their balance sheets for bad mortgage debts rose sharply in the middle of 2020, they’ve since trended downwards – hinting that the lenders aren’t overly stressed about any risks in the system. Similarly, the non-performing housing loan ratios (up to 90 days overdue plus more than 90 days/impaired loans as % of total) across the banks are also super low and mortgagee sales very rare. On the latest figures we have, only 0.2% of housing loans in the banking system are non-performing.

Either way, when all is said and done, the changes have nevertheless been made and everybody will need to adjust. And certainly, a prudent approach to mortgage lending can’t be a bad thing if it prevents excessive risk taking which might sow the seeds of a future financial crisis.

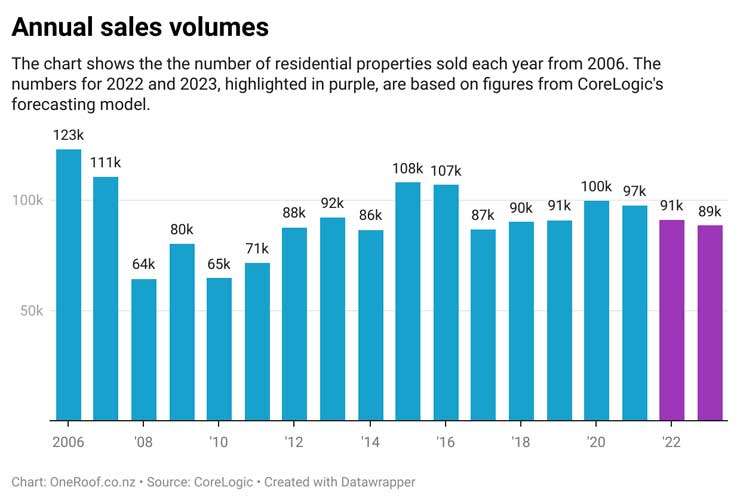

In terms of the implications for property sales volumes and value growth, it’s hard to see anything other than a slowdown this year – especially when you also factor in pre-existing affordability problems. Indeed, our forecasting model (which looks at drivers such as wages, GDP, migration, and mortgage rates) points to a drop in sales volumes from around 97,500 in 2021 to about 91,000 this year and 88,500 in 2023 (compared to long-run norm of about 97,000). If anything, the difficulty of capturing credit conditions in a numerical model suggests that the risks are to the downside too.

As sales volumes slide lower but new listings flows at the start of the pipeline hold up (or perhaps even increase further if say some investors can’t make the sums work with rising costs but low gross rental yields), it’s also on the cards that vendors will lose some pricing power this year and we could see something of a switch to a buyer’s market – especially with the amount of new construction still so high. Put another way, more choice for buyers implies less upwards price pressure. Indeed, value growth looks set to slow from more than 25% in 2021 to low single digits this year, with a fall in values also possible if unemployment started to rise.

Who might win or lose in this environment? Clearly, anybody looking to get a mortgage will find it tougher going as credit supply tightens and interest rates go up – including first home buyers, mortgaged investors, but also even other owner occupiers with already-large mortgage who are looking to trade up to a bigger or better-located property.

On the flipside, owner occupiers with plenty of equity who are perhaps looking to downsize or move to a cheaper location could come out nicely, while there could also be opportunities for cash investors. True, gross rental yields for investors are still low, whether you have lots of equity or lots of debt. But some cash investors will still no doubt view the yields on particular property deals as better than the alternatives (e.g. term deposits), especially if they can get a sneaky offer accepted to buy the property in the first place.

• Kelvin Davidson is chief economist at CoreLogic